Shortly after Ursula K. Le Guin died — 5 or 6 weeks ago now — I read a new book by her. And by “new” I mean she published it in 1976, and my wife has had it since the eighties, and I had never seen it before. It’s also not science fiction/fantasy. It’s a ’70s young adult novel. And it contains some profundities.

Very Far Away from Anywhere Else:

Very Far Away from Anywhere Else:

(p. 17) The reason I have reported that conversation with Natalie Field on the bus so exactly is that it was an unimportant conversation that was extremely important to me. And that’s important, that something unimportant can be so important.

(p. 31) She was hard to answer. But not the way my parents were. They were hard to answer because you could never get to the real point with them, and she was hard to answer because she’d got there first.

(p. 41) We didn’t talk about problems, or parents, or automobiles, or ambitions. We talked about life. We decided that it was no good asking what is the meaning of life, because life isn’t an answer, life is the question, and you, yourself, are the answer.

I find that the last quote is one I’ve seen before; it resonates, deep within me. I don’t know where I read it; I just know this is the first time I’ve seen it in context!

—–

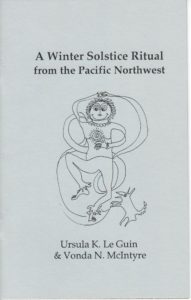

I have another book of hers, a chapbook, that I haven’t looked at in a long time. I went to find it today. Safely contained in a publisher’s envelope placed between two sturdy pieces of cardboard in a zip-lock bag, with the original wrapping paper, in, further, a gift bag hanging up on a hook in a closet of linens and more wrapping paper,* is a doubly-signed copy of A Winter Solstice Ritual from the Pacific Northwest, by Ursula K. Le Guin and Vonda N. McIntyre (illustrated by Ursula K. Le Guin). It was a double birthday present, about 10 years ago.**

I have another book of hers, a chapbook, that I haven’t looked at in a long time. I went to find it today. Safely contained in a publisher’s envelope placed between two sturdy pieces of cardboard in a zip-lock bag, with the original wrapping paper, in, further, a gift bag hanging up on a hook in a closet of linens and more wrapping paper,* is a doubly-signed copy of A Winter Solstice Ritual from the Pacific Northwest, by Ursula K. Le Guin and Vonda N. McIntyre (illustrated by Ursula K. Le Guin). It was a double birthday present, about 10 years ago.**

For some reason, there are very few parts in this ritual that remind me in any way of solstice rituals I have actually attended. But perhaps this is because I haven’t spent any time in the Pacific Northwest. I’m sure it is a very different place and has many of its own quirks.

Such as these:

(p. 1) To Begin the Ceremony: First, take the remaining truffles from the pigs. Eat the truffles. After this, participants in the rites are expected to fast throughout the entire ceremony, though they may if they feel faint partake of oysters (halfshell or Rockefeller), salmon (dried, smoked, broiled, or wine-poached), champagne, chocolate truffles, vanilla ices, sherbets, root beer, and Metamucil.

(p. 4) Further Optional Rituals, to ensure that the days do start getting longer again:

(p. 4) Further Optional Rituals, to ensure that the days do start getting longer again:

Choral whining

Improvisational Limericks

Staying up later and later, or getting up earlier and earlier

Petting of the large grey cats, followed by interpretation of the cat drool (feliguttamancy)

(p. 7) Blessing the Ground: At dusk, a little brown VW Beetle full of little brown bats is driven slowly once around the temenos. As night falls, the little brown bats are released to eat little brown bugs. If the bats are hibernating and will not fly, they are to be hung in festoons from the eaves of the small house on the east side of the village.*** The most desirable drivers of the Sacred Beetle are Little, Brown authors, if available.

(Mmm, chocolate truffles.)

—–

And, finally, The Annals of the Western Shore.****

I went to a reading in early 2006, in which Ursula read a passage from a forthcoming YA fantasy novel; it was awesome to hear her read, and it was a vivid, intense scene. There’s a kid, and she’s in the marketplace, and a horse is spooked by a “halflion” (or perhaps by the crowd spooked by the lion?) and she manages to grab and quiet the horse and thus meets the companions of the halflion, who then accompany her to her home.

So then I went home and tried to find the book online. Nothing. Well, it hadn’t come out yet. Wait, try again. Nothing. Ursula K. Le Guin. YA. Halflion. Nothing. At least, nothing recognizable.

Eventually, and not too much later, I did find (or realise I had found) the book. It’s called Voices, and it’s second in the Annals of the Western Shore trilogy, and it was published in September of 2006. And while the scene she read to us was vivid and powerful and pivotal in the arc of the story … it turned out that the halflion did not appear in any of the prepublication marketing.

Eventually, and not too much later, I did find (or realise I had found) the book. It’s called Voices, and it’s second in the Annals of the Western Shore trilogy, and it was published in September of 2006. And while the scene she read to us was vivid and powerful and pivotal in the arc of the story … it turned out that the halflion did not appear in any of the prepublication marketing.

Here are quotes from the Annals, which I have shared once before. And, as it happens, the halflion doesn’t appear in any of my quotes, either.

(The following section is adapted from a 2008 post on the Big Blue Marble Bookstore blog.)

The three passages below are from Ursula Le Guin’s recent Annals of the Western Shore series. It’s not actually one quotation from each book; two are from Voices (book 2), which I have now declared my very favorite of her books that I’ve read. The third is from the third book, Powers. The whole series, starting with the first book, Gifts, touches on questions of power: what it means, how to recognize it, and how to use (or not use) it. The books all have different main characters, in different settings and times, but each of those characters becomes significant to the story arc of the following books (rather like the Earthsea Cycle), letting it feel more like continuity than a loss of it.

“I’m sorry, now, for that girl of fifteen who wasn’t as brave as the child of six, although she longed as much as ever for courage, strength, power against what she feared. Fear breeds silence, and then the silence breeds fear, and I let it rule me. Even there, in that room, the only place in the world where I knew who I was, I wouldn’t let myself guess what I might become.”

– Voices (Annals of the Western Shore, book 2)

“I always wondered why the makers leave housekeeping and cooking out of their tales. Isn’t it what all the great wars and battles are fought for—so that at day’s end a family may eat together in a peaceful house? The tale tells how the Lords of Manva hunted and gathered roots and cooked their suppers while they were camped in exile in the foothills of Sul, but it doesn’t say what their wives and children were living on in their city left ruined and desolate by the enemy. They were finding food too, somehow, cleaning house and honoring the gods, the way we did in the siege and under the tyranny of the Alds. When the heroes came back from the mountain, they were welcomed with a feast. I’d like to know what the food was and how the women managed it.”

– Voices (Annals of the Western Shore, book 2)

“The first true leader I knew was this boy of seventeen, Yaven Altanter Arca, and I have judged others by him. By that standard, leadership means personal magnetism, active intelligence, unquestioning acceptance of responsibility, and something harder to define: a tension between justice and compassion, which is never truly satisfied by one without the other, and so can seldom be wholly satisfied.”

– Powers (Annals of the Western Shore, book 3)

———————

*With a sign on the door saying “Beware of the leopard”. (More Douglas Adams on the brain.)

**Thanks, Vix!

***Note: This book is from 1991. I’d like to hope that in these days of white nose syndrome people would think twice before festooning a house with hibernating bats. Also, are there bugs at the winter solstice in the Pacific Northwest?

****Okay, not quite finally. I do want to mention Catwings, her beautifully illustrated series for very young readers. I don’t have any specific quotes from it. I just want to mention how compelling it is, and its charm and silliness and wisdom. And how books 2 and 3 incorporate trauma theory, which is not something you get in every book written for this age. My kid loves them, now that I have located my copies for him — they were a much earlier birthday present.***** This took a lot more searching and cogitating than finding the chapbook: I found myself completely at a loss looking for it (not under kids’ books, not with her other books in SF/F), until I finally remembered that I actually have a number of my books shelved together under Cats.

****Okay, not quite finally. I do want to mention Catwings, her beautifully illustrated series for very young readers. I don’t have any specific quotes from it. I just want to mention how compelling it is, and its charm and silliness and wisdom. And how books 2 and 3 incorporate trauma theory, which is not something you get in every book written for this age. My kid loves them, now that I have located my copies for him — they were a much earlier birthday present.***** This took a lot more searching and cogitating than finding the chapbook: I found myself completely at a loss looking for it (not under kids’ books, not with her other books in SF/F), until I finally remembered that I actually have a number of my books shelved together under Cats.

*****Thanks, sweetie!

On the topic of such presents: For my most recent birthday I requested and received another book by Le Guin, one which is actually new, published last year: Words Are My Matter: Writings About Life and Books, 2000-2016. I’m working my way through it now. Learning a lot.

Very Far Away from Anywhere Else:

Very Far Away from Anywhere Else: I have another book of hers, a chapbook, that I haven’t looked at in a long time. I went to find it today. Safely contained in a publisher’s envelope placed between two sturdy pieces of cardboard in a zip-lock bag, with the original wrapping paper, in, further, a gift bag hanging up on a hook in a closet of linens and more wrapping paper,* is a doubly-signed copy of A Winter Solstice Ritual from the Pacific Northwest, by Ursula K. Le Guin and Vonda N. McIntyre (illustrated by Ursula K. Le Guin). It was a double birthday present, about 10 years ago.**

I have another book of hers, a chapbook, that I haven’t looked at in a long time. I went to find it today. Safely contained in a publisher’s envelope placed between two sturdy pieces of cardboard in a zip-lock bag, with the original wrapping paper, in, further, a gift bag hanging up on a hook in a closet of linens and more wrapping paper,* is a doubly-signed copy of A Winter Solstice Ritual from the Pacific Northwest, by Ursula K. Le Guin and Vonda N. McIntyre (illustrated by Ursula K. Le Guin). It was a double birthday present, about 10 years ago.** (p. 4) Further Optional Rituals, to ensure that the days do start getting longer again:

(p. 4) Further Optional Rituals, to ensure that the days do start getting longer again: Eventually, and not too much later, I did find (or realise I had found) the book. It’s called Voices, and it’s second in the Annals of the Western Shore trilogy, and it was published in September of 2006. And while the scene she read to us was vivid and powerful and pivotal in the arc of the story … it turned out that the halflion did not appear in any of the prepublication marketing.

Eventually, and not too much later, I did find (or realise I had found) the book. It’s called Voices, and it’s second in the Annals of the Western Shore trilogy, and it was published in September of 2006. And while the scene she read to us was vivid and powerful and pivotal in the arc of the story … it turned out that the halflion did not appear in any of the prepublication marketing. ****Okay, not quite finally. I do want to mention Catwings, her beautifully illustrated series for very young readers. I don’t have any specific quotes from it. I just want to mention how compelling it is, and its charm and silliness and wisdom. And how books 2 and 3 incorporate trauma theory, which is not something you get in every book written for this age. My kid loves them, now that I have located my copies for him — they were a much earlier birthday present.***** This took a lot more searching and cogitating than finding the chapbook: I found myself completely at a loss looking for it (not under kids’ books, not with her other books in SF/F), until I finally remembered that I actually have a number of my books shelved together under Cats.

****Okay, not quite finally. I do want to mention Catwings, her beautifully illustrated series for very young readers. I don’t have any specific quotes from it. I just want to mention how compelling it is, and its charm and silliness and wisdom. And how books 2 and 3 incorporate trauma theory, which is not something you get in every book written for this age. My kid loves them, now that I have located my copies for him — they were a much earlier birthday present.***** This took a lot more searching and cogitating than finding the chapbook: I found myself completely at a loss looking for it (not under kids’ books, not with her other books in SF/F), until I finally remembered that I actually have a number of my books shelved together under Cats.

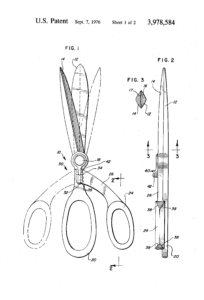

I recently requested, and acquired, a pair of left-handed scissors for my office. I was pleased to discover, with a quick search, that it was possible to order explicitly left-handed titanium-bonded scissors that exactly matched the scissors in the copy room cabinets. In fact, as I discovered when they arrived, they say “LEFTY” only on the package and not on the scissors, which say merely “Westcott titanium” and are therefore indistinguishable from the right-handed scissors except for the orientation of the blades. I held them up together to check. And then, alas, I had to check the other right-handed scissors in the cabinet to make sure I took my own set back to my office.

I recently requested, and acquired, a pair of left-handed scissors for my office. I was pleased to discover, with a quick search, that it was possible to order explicitly left-handed titanium-bonded scissors that exactly matched the scissors in the copy room cabinets. In fact, as I discovered when they arrived, they say “LEFTY” only on the package and not on the scissors, which say merely “Westcott titanium” and are therefore indistinguishable from the right-handed scissors except for the orientation of the blades. I held them up together to check. And then, alas, I had to check the other right-handed scissors in the cabinet to make sure I took my own set back to my office. And why shouldn’t I trust the marketing? I’m so glad you asked. I don’t trust the marketing because Things Have Changed in scissor handedness world. For example, I’ve asked whether there are left-handed scissors available for my kid in a craft situation, and I’ve been told that all the scissors should work for both hands. And when I dismiss this as ridiculous, and go off to find scissors (for kids or grownups) in an office supply store, I find packages that actually, explicitly say “left or right handed”.

And why shouldn’t I trust the marketing? I’m so glad you asked. I don’t trust the marketing because Things Have Changed in scissor handedness world. For example, I’ve asked whether there are left-handed scissors available for my kid in a craft situation, and I’ve been told that all the scissors should work for both hands. And when I dismiss this as ridiculous, and go off to find scissors (for kids or grownups) in an office supply store, I find packages that actually, explicitly say “left or right handed”.

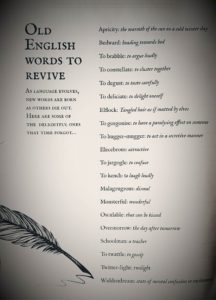

A couple of months ago, a friend posted a list** of “Old English Words to Revive,” and I was charmed to see that the first word on the list was “apricity”.

A couple of months ago, a friend posted a list** of “Old English Words to Revive,” and I was charmed to see that the first word on the list was “apricity”.